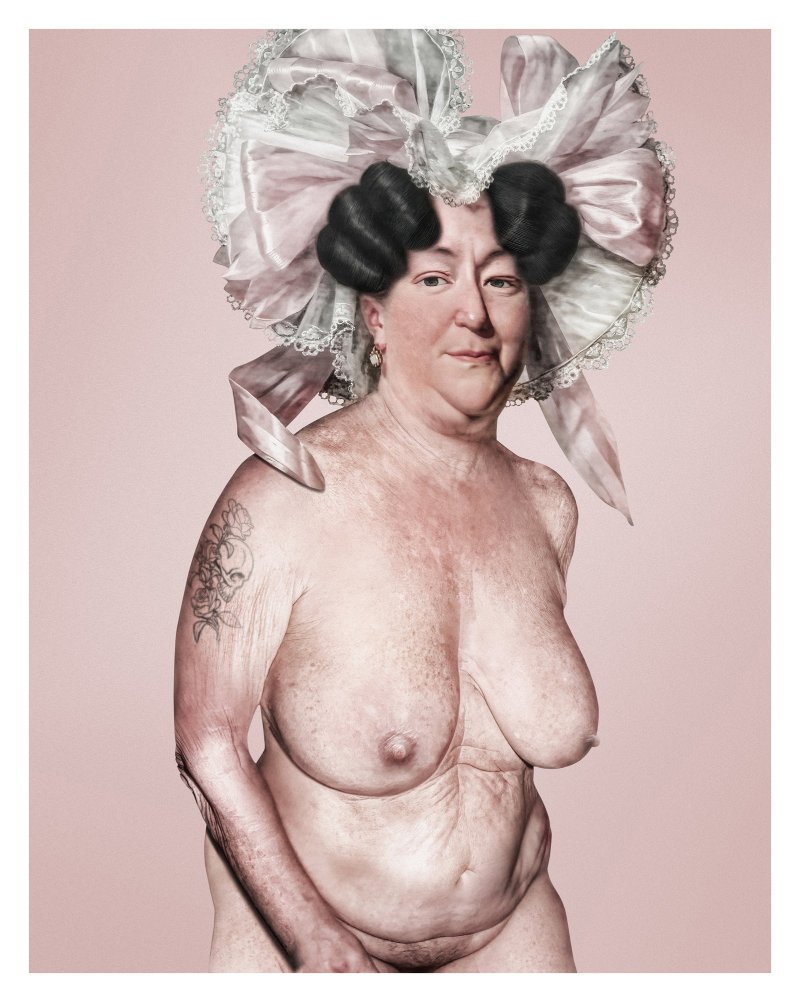

Lars Hifling: Reframing art history from a queer perspective

Ordinary People No2

How has art helped us shape our perception of history? And is that perspective accurate? These are the questions that I started with as I began researching for this article.

Now, as the title suggests, this article is largely my interview with the Danish artist Lars Hifling, whose artwork essentially blows apart those two questions—at least from a straight white male perspective—so I wanted to do my homework before presenting myself.

And this is where I would like to digress for a second to admit an embarrassing realization that didn't occur to me until I started my research.

“Humanity has always involved queerness, but history has always been straight.”

Now, this is reducing a very complex issue to a base and over-simplistic statement—but it is fundamentally true.

To illustrate, there are artworks spanning back over 10,000 years that record images of homosexuality. Going further, I discovered during my research a fascinating presentation by Liz Bradbury on Art & History from a Queer Perspective that further illustrates this point by looking at the Italian Renaissance. Yet, global acknowledgment and discourse about LGBTQIA+ equality are less than half a century old. Not that queer discourse has never existed preceding the last century, but more than any discourse has been largest erased from history.

In hindsight, this realization seems rather obvious and colored by my straight male privilege—thus the reason for my embarrassment.

Understanding this now, one might go so far as to say that while "history has been written by the victors," it seems that queer hands have been significantly influential in shaping the history of art—if not from behind the veils of secrecy.

This subject matter, or in Lars' words, the "queering and reclaiming history from a queer perspective," is at the core of his work. It was present in the work I first encountered during his solo exhibition, Ordinary People, at ROS Gallery. It led me to ponder my perspective on how art has helped shape our historical perspective and reach out to Lars’ to get his perspective on why history’s recordings are wrong.

Ordinary People No1

INTERVIEW

You’ve written that your work reevaluates the images of the past from a Queer perspective. Can you tell me more about that?

You could probably call my work a kind of digital collage, where I combine the past with the present and explore how cultural narratives are structured and unfolded over time. The past may be dead, but history is alive, and what’s important is that history is being constructed and written in the present.

That is why queering and reclaiming history from a queer perspective are important to me.

This does not mean that my art should be seen as a scientific rewriting of history, but rather as construction where I cast a subjective "queer glance" at art history and reinstate the themes that have always been there in a more or less hidden way. My works do not necessarily represent the truth, but the point is that neither do the old paintings you see in museums. There are so many stories and identities behind the artists and the people you see in old paintings, which are concealed or suppressed by the norms of the time.

When you look at the history of art with a queer eye, you discover that history is not just a record of the past but also an erasure of specific events and identities. This applies to women as well as to all minorities. Systematic repression and censorship of homosexuality over the centuries have displaced countless human stories from our collective memory.

I Don’t Want to Die Poor No3

Since the fall of the Roman Empire and the rise of Christianity, queer people have been forced to hide their identities. That's why it can be challenging to find evidence of queer art. The queer artists were forced to develop sophisticated codes and express their identities through paraphrases that only the initiated could decode. And in this way, you can say that art worked for the queer communities of the past as the world's first encrypted messages.

When I look at your work, I think there are these resonating tones of satire, sexuality, and political statement. How does that make you feel?

I think that you are spot on!

"Everything is about sex, except sex. Sex is about power,” Oscar Wilde said. And power structures, sexuality, and masculinity have always been recurring themes in my art.

Regarding satire and humor, I see it as an essential part of life and an effective way of communicating with others.

In the series I Don't Want To Die Poor, I have taken the faces and assets of wealthy and influential people from the past and merged them with the bodies of living people. The series is deliberately funny and the title ironic, but at the same time, it asks questions about life, death, and consumerism.

And so you might say that my works are political, yes. Political in the way that I see my artistic practice as a kind of investigation where I ask existential and political questions.

For instance, many of my works explore gender roles and male identity.

I Don’t Want to Die Poor No.2

Looking at the male ideal through art history, you quickly discover that it has changed dramatically. In portraits from the 18th century, you see the rich and powerful men portrayed with wigs and brightly colored silk robes, bows, and ribbons. That is very far from the ideal of the modern, masculine man with a beard, short-cut hair, and a dark suit. This idea arose in the 19th century and continues to dominate as the epitome of a "real man."

Art history, however, shows us that male identity and masculinity are fluid concepts constantly changing. And it shows us that the people who claim that there is only one way to be a real man are wrong. Even more importantly, it shows us that if we see ourselves from a historical perspective, we get the chance to see ourselves from a different perspective.

You work with the digital medium of photography, so tell me more about the process of how you create your work.

My work is produced on a computer, but the process is manual. The figures I use from old paintings are the foundation of an artwork, and whenever I've got an idea for a series, I start searching for figures from classical art.

Then I digitally cut out the figures from their backgrounds and start retouching them. It takes quite a long time because there may be cracks in the painting or something in front of a figure that I need to remove.

The contemporary figures in my works come from the Internet. However, if you look more closely at those figures, they are not just people I take directly from the Internet and insert them into my art.

I Don’t Want to Die Poor No.6

Each present figure in my works consists of many different people. A person's upper body comes from one person, the arm comes from another, and the hands and legs come from a third and fourth. So in this way, I kind of build the bodies in the poses that I want.

The faces of the figures are always composed of faces from different people. The eyes from one person, nose from another, mouth from a third, and so forth, until they get the expression I want. A work of mine can consist of 30 or more photos. All contemporary figures are composed of many images of facial and body parts, thus wholly fictitious—a kind of handmade deep fake.

When I have finished the retouching and composition of the figures, I start working on the lighting. As you can see in some of my works, the dramatic light used by the old masters such as Caravaggio and Rembrandt often inspires me. The photos I use from the internet are always lit neutrally without shadows. Therefore, I add the light and shadow to the figures in Photoshop, using a digital brush to paint shadows and lights on each figure.

So, in a way, my works are not only digital collages or photos or classic oil paintings, but a mixture of all of them and also a kind of digital painting.

And for my final question, where do you see the future trajectory of your conceptual and artistic processes?

I don't exactly know where my art will take me in the future.

I always start with a concrete idea and a specific concept in my work. But often, the process takes a turn, and I end up in a completely different place than planned, as if art has its own will and is more intelligent than I am.

And that is precisely what makes working as an artist so fascinating. Because you ask a question without knowing the answer and never know where the next project will take you.